How to choose the highest quality image format in 2026?

Updated: January 19, 2026 Author: Vitaly

This article takes a detailed look at how image quality requirements have changed with the advent of HDR, wide color gamuts, and OLED displays. You'll learn why resolution is no longer the primary indicator of quality. This article covers key formats for photography and the web, examining their real-world advantages, limitations, and application scenarios.

In an era of ever-increasing visual data volumes, the concept of "highest image quality" is no longer defined solely by resolution or the absence of visible artifacts. This is due to the rapid development of display technologies such as HDR and Wide Color Gamut, as well as the widespread adoption of OLED displays. Quality is now determined by a combination of parameters: accuracy, color depth, dynamic range, encoding efficiency, and resistance to degradation during repeated processing.

2026 promises to be a year of fundamental change, when established image format standards that ensure maximum compatibility (JPEG, TIFF) will begin to be replaced by new, revolutionary solutions (JPEG XL, AVIF). Therefore, understanding these changes is more important than ever, so as not only to remain competitive but also to optimize the storage of existing digital assets.

Modern requirements for image quality

Before we move on to analyzing specific formats, it's important to define the technical metrics that make up the concept of "highest quality" and that are relevant to both professional and home photography.

Bit depth and dynamic range

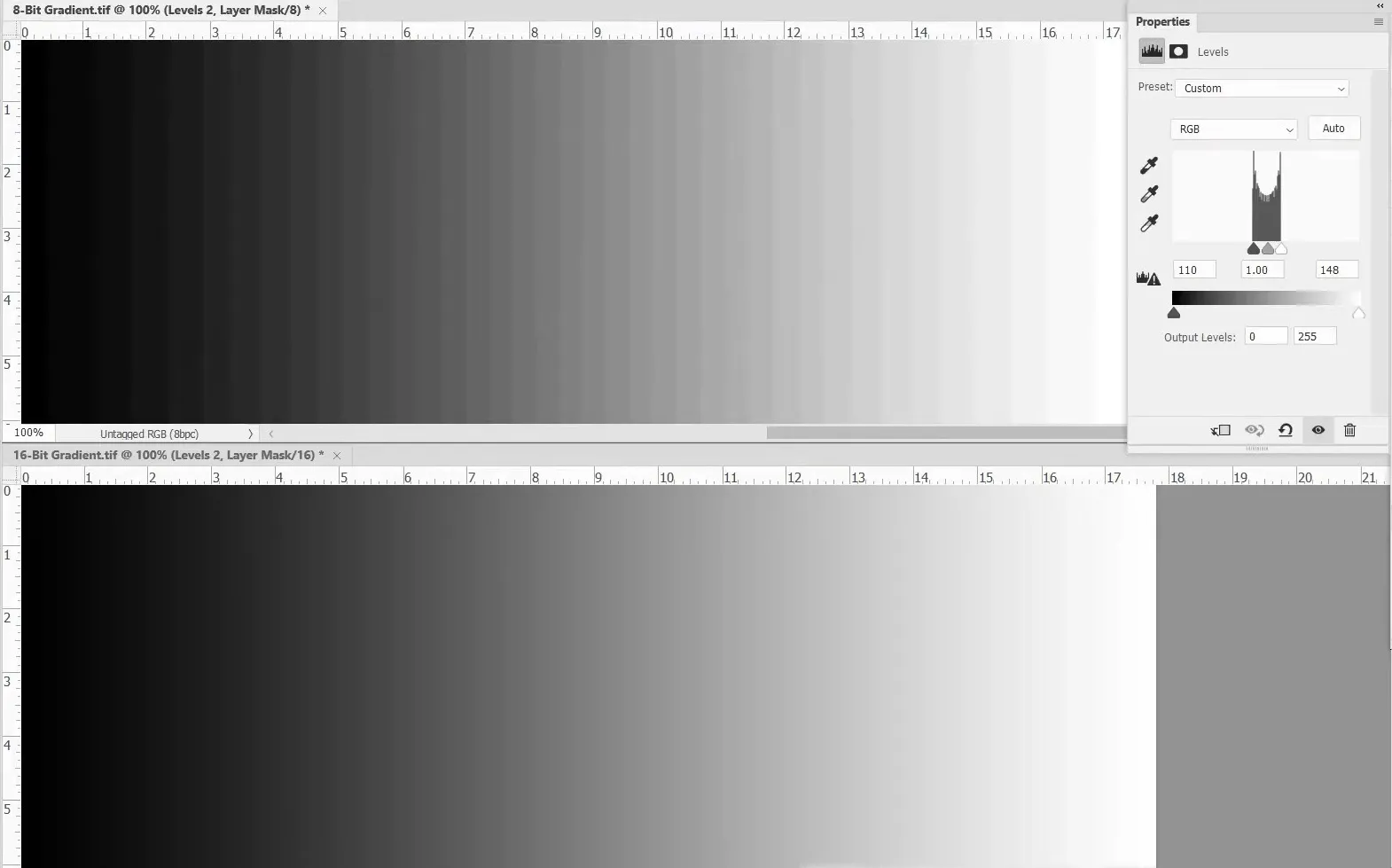

Traditional 8-bit formats (standard JPEG) can only display 256 gradations of brightness per channel, which is insufficient for modern displays and professional processing. Highest quality today requires the use of:

- 10–12 bit. The minimum standard for HDR (High Dynamic Range) content, which avoids banding (stepped gradients) in the sky and ensures smooth color transitions.

- 16-bit. The standard for professional photography, it encompasses 65,536 levels per channel and 281 trillion colors. The human eye can't discern the difference between 12 and 16 bits during normal viewing, but for a computer, it makes a huge difference during mathematical editing operations. The difference is especially noticeable when processing dark photographs.

- 32-bit floating-point. Necessary for VFX (visual effects) and scientific data, where luminance values may exceed the conventional "white" (1.0) to simulate real-world physical light. This allows for the description of the dynamic range of the real world—from the pitch-black cave to a nuclear explosion—in a single file.

Color gamut

If bit depth (8, 10, 16 bits) determines the number of steps (gradations) from black to white or from red to deep red, then color gamut defines the boundaries of these colors. This gamut determines how close the most saturated red, green, or blue color in a file is to the actual color.

sRGB has long been the standard for displays, but it only covers about 35% of the spectrum visible to the human eye. Anything outside its range is simply "cut off" to a dim equivalent.

Display P3 is the modern standard for the film industry and most high-quality displays (Apple iPhone/MacBook, Google Pixel, OLED TVs). It covers 25% more colors than sRGB. The difference in red and green tones is particularly noticeable. A photograph of a sunset or spring foliage looks vibrant on a P3 display, while flat on an sRGB display.

Rec.2020 is the color reproduction standard for 4K/8K HDR images. It covers approximately 75% of the visible spectrum. Most modern monitors are not yet capable of displaying it in full (they typically cover 70–90% of Rec.2020), but this format provides headroom for the future.

Compression type

When it comes to high-quality images, there are only two approaches to data compression used in practice:

- Lossless. It works on the same principle as ZIP archives. The algorithm finds repeating fragments of data and writes them more compactly, without discarding a single bit of information. After unpacking, the image is completely identical to the original, down to the last pixel. The downside is that the files themselves are large.

- Visually lossless. In this case, the algorithm relies on the characteristics of human vision. It removes or simplifies details that the eye is practically unable to discern: fine noise, minor color transitions, and detail in extremely dark or overexposed areas. The resulting image is technically altered, but visually it remains just as sharp and detailed.

Most modern high-quality image formats are based on visually lossless image compression. This approach allows file sizes to be reduced by 10-50 times compared to uncompressed images, while maintaining a visual appearance that appears identical to the original to the user.

Highest quality image formats for photographs

When choosing an image format for long-term photo storage, it's important to balance quality, capacity, and future technological availability. The specific type of images to be preserved is also crucial. For professional photographers, it's important to preserve not only the final product sent to the client but also the original negatives.

For private users, the challenge isn't the format, but the organization. For them, preserving all the metadata used by cataloging programs for sorting is critical.

Choosing a format for professional work and archiving

Camera manufacturers (Canon, Sony, Nikon, Fujifilm) have traditionally used proprietary formats to store raw sensor data (CR3, ARW, NEF). These files contain precise values obtained from the sensor's photodiodes, but the processing methods used to process them remain a trade secret.

The closed nature of formats creates certain compatibility risks in the future. For example, if the format changes (from NEF to NEF2 or from CR2 to CR3) or support for older models is discontinued, converters may not process the files correctly.

An alternative is Adobe's open DNG standard, based on TIFF, which is offered as a long-term storage solution. Unlike proprietary RAW formats, DNG stores not only sensor data but also information about how it should be interpreted: color matrices, camera profiles, and white balance settings. This reduces the risk of future incorrect processing and makes the results less dependent on software.

Furthermore, DNG uses more efficient lossless compression, saving up to 20% of disk space. Therefore, many photographers use DNG for backups when converting RAW files. The question remains: "Is it necessary to do this at all?"

Preserving original files is worth it if they have long-term value. In commercial and advertising photography, they are often part of the production process, allowing access to them years later for new materials or retouching. In this case, long-term storage is justified.

In private photography (portraits, family, and weddings), the situation is different. Ready-to-use JPEG or TIFF files are usually sufficient to meet clients' needs. Repeat processing requests are rare, and storing RAW archives increases data volume without providing any tangible benefit. Therefore, avoiding storing the original files or converting them to DNG seems a more reasonable solution from a technical and economic perspective.

Ready-made photos and mobile photography

By 2026, mobile photography will no longer be a compromise between convenience and quality. Modern smartphones are equipped with multi-element sensors with a high dynamic range. In typical shooting conditions (daylight, HDR scenes, portraits), they can deliver image quality comparable to non-professional cameras and even some mirrorless cameras. This is achieved not by the physical size of the sensor, but by the use of algorithms: multi-frame HDR, noise reduction, and tone mapping.

At the same time, modern flagship smartphones can now shoot in DNG (RAW), providing access to the sensor's raw data without aggressive processing. This brings mobile and traditional photography closer together.

However, most users don't use DNG for everyday photography. Until recently, JPEG dominated, but with the release of modern devices with HDR displays and bit depths exceeding 8 bits, the format's technical limitations have become more apparent. A search for alternatives has arisen.

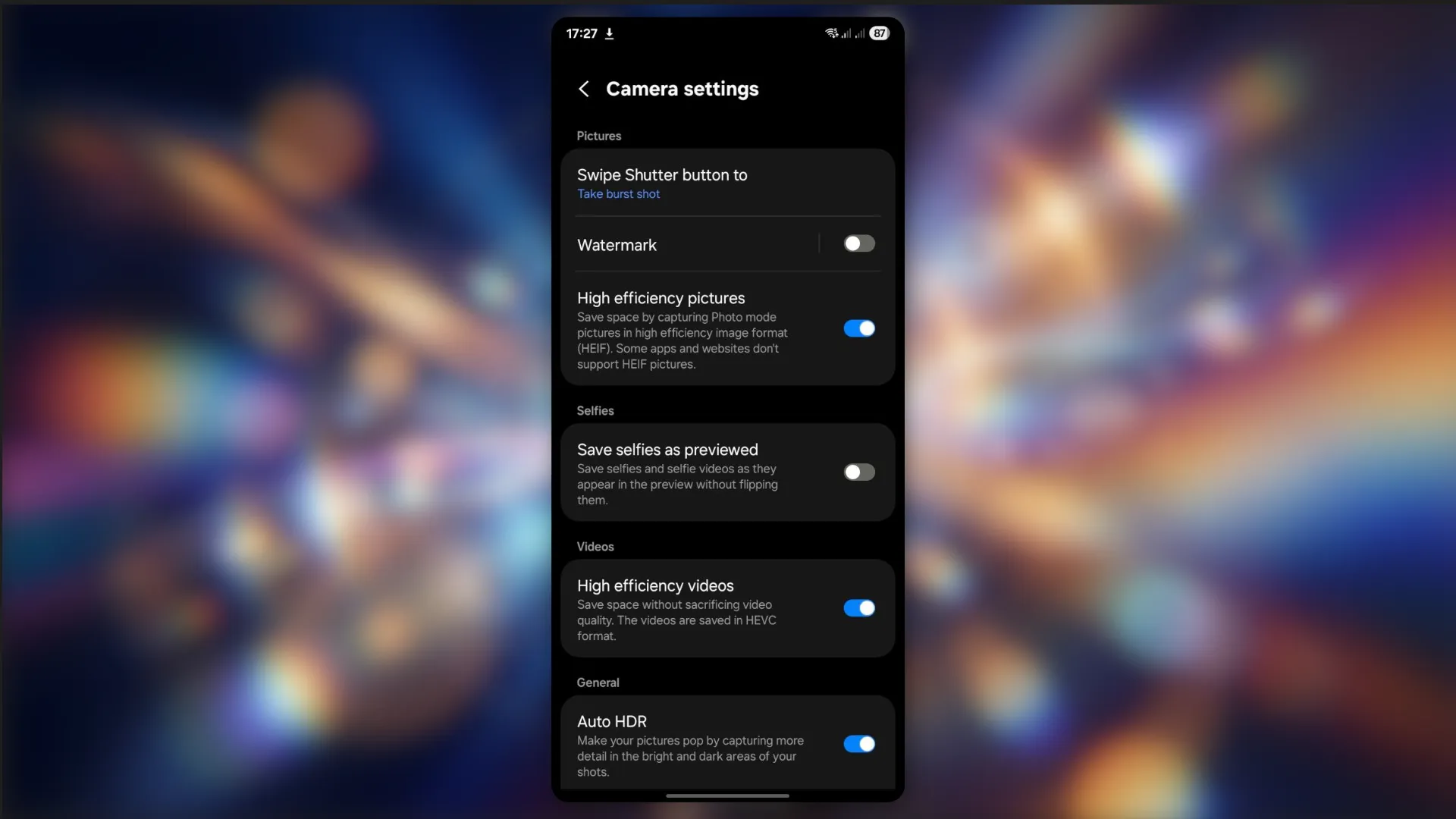

HEIC

HEIC has been the default format for iPhone photos since 2017. It supports depth maps, Live Photos, and HDR. Its use of a modern codec ensures excellent compression. HEIC files are typically 40–50% smaller than JPEG files with the same level of visual quality.

Late 2025 and early 2026 marked a turning point for this format. HEIC is now available not only to iPhone users but has also begun to actively integrate into the Android ecosystem, primarily affecting mid-range and premium devices.

JPEG XL

JPEG XL is the most modern image format, developed as a direct replacement for JPEG. In terms of compression, it demonstrates significant efficiency gains over previous formats:

- compared to JPEG, the file size is reduced by an average of 30–50% with visually identical quality;

- 8 Compared to HEIC, JPEG XL performs 10-20% better, especially on complex scenes such as night shots, images with noise, fine textures, and smooth gradients.

In practice, this means that an image that takes up 4 MB in JPEG will weigh around 2-2.4 MB in HEIC and around 1.8-2.2 MB in JPEG XL, with comparable visual quality.

At the same time, JPEG XL supports color depth up to 16 bits per channel with HDR, which is especially noticeable in photos with skies, skin, fog, and night scenes.

High-quality image formats for the web

The internet is a highly contentious medium, where instant loading times are needed on the one hand, and cinematic image quality on the other. Before the advent of high-dynamic-range displays, JPEG was sufficient to meet both requirements. However, as image quality demands increased, the need for new, more efficient formats arose.

WebP

Developed by Google in the early 2010s, WebP became an industry standard by 2026. It offers 25–35% more efficient data compression than similar JPEG or PNG images with comparable quality.

Despite its superiority over older formats, its compression algorithms (based on the VP8 video codec) are prone to loss of shadow detail and smoothing of skin texture. This makes WebP unsuitable for high-quality photography. Furthermore, the format is limited to a strictly 8-bit per channel and therefore does not support HDR, which requires a minimum of 10-bit.

WebP lacks progressive rendering, where image quality improves as the browser receives data. This is due to VP8, which wasn't optimized for static images. It works by predicting pixel blocks, and this process is technically linear. The data in a WebP file is packed in such a way that it can only be decoded sequentially. As a result, a poorly optimized website can cause loading speed issues.

AVIF

Unlike WebP, AVIF was not created as a format for web images, but as a response to HEIC, so it was initially more focused on photographs and high-detail implementation.

Supporting 10 and 12 bits (versus 8 bits in WebP/JPEG), it allows for billions of colors to be rendered without jaggies (banding) in gradients. However, AVIF's aggressive high-frequency noise removal negatively impacts the visual perception of images. Photos with film grain, fabric texture, or asphalt texture often look "plasticky."

Like WebP, AVIF does not support progressive decoding. As a result, the image does not appear until a significant portion of the file has downloaded. However, this is not a significant issue when using the format for simple graphic elements, interfaces, and small illustrations, where it is most widely used.

JPEG XL

Beyond photographs, JPEG XL (JXL) could become the new web standard, replacing the older JPEG. It implements a unique encoding architecture (VarDCT), which allows a full-size preview of an image to be displayed after only 10-15% of the data has been downloaded. This is particularly beneficial for improving the Large Contentful Paint (LCP) metric and user perception of loading speed.

Unlike video-oriented codecs (WebP, AVIF), JXL is designed specifically for static images and preserves texture and grain much more naturally.

JPEG XL allows you to take an existing library of JPEG files and convert them to JXL, reducing their size by 20% without losing a single pixel of information. The process is reversible, making it ideal for CDNs (Content Delivery Networks), which can store a single JXL file and serve the JPEG to legacy clients on the fly.

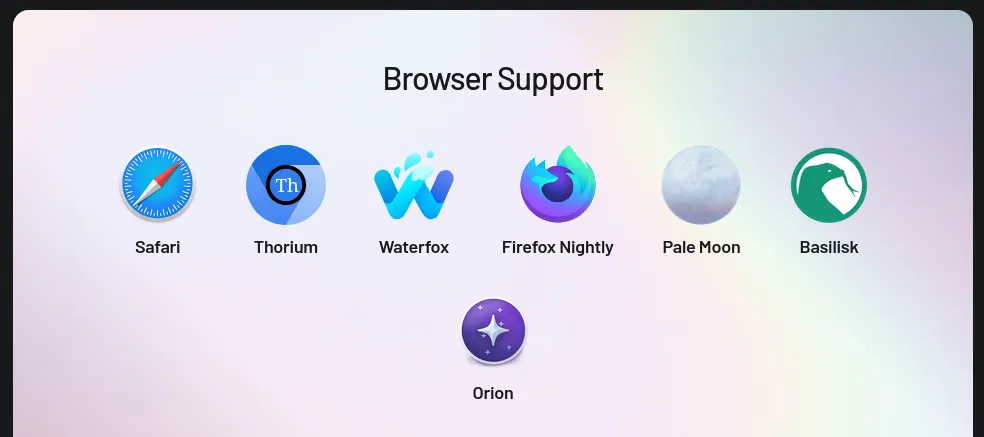

JPEG XL's only drawback is its low adoption. Native support for the format is limited to the Apple ecosystem, as well as Linux distributions running KDE Plasma or GNOME desktop environments. The situation is similar in browsers: aside from Safari, JPEG XL only works natively in a few versions of Firefox and Chromium.

However, the situation could change dramatically in 2026. Following its dramatic removal from Chrome in 2022 and subsequent reinstatement of support in late 2025, JPEG XL has every chance of establishing itself as the industry standard for the web.

Converting Image Format: A Practical Approach

Choosing the "ideal" image format is pointless without understanding how it will be used in practice. In real-world work, conversion is often necessary:

- prepare photographs for publication on the website;

- reduce file size without quality degradation;

- convert images to a format supported by the CMS;

- save metadata (EXIF, GPS, shooting date) for subsequent cataloging;

- process not a single file, but an entire archive at once.

Of course, you can skip the hassle and simply use well-known tools. Most image conversion utilities (ImageMagick, XnConvert, CLI tools) handle the task of transcoding perfectly. However, they solve a narrow technical problem: pixel conversion.

Tonfotos: Conversion as part of the workflow

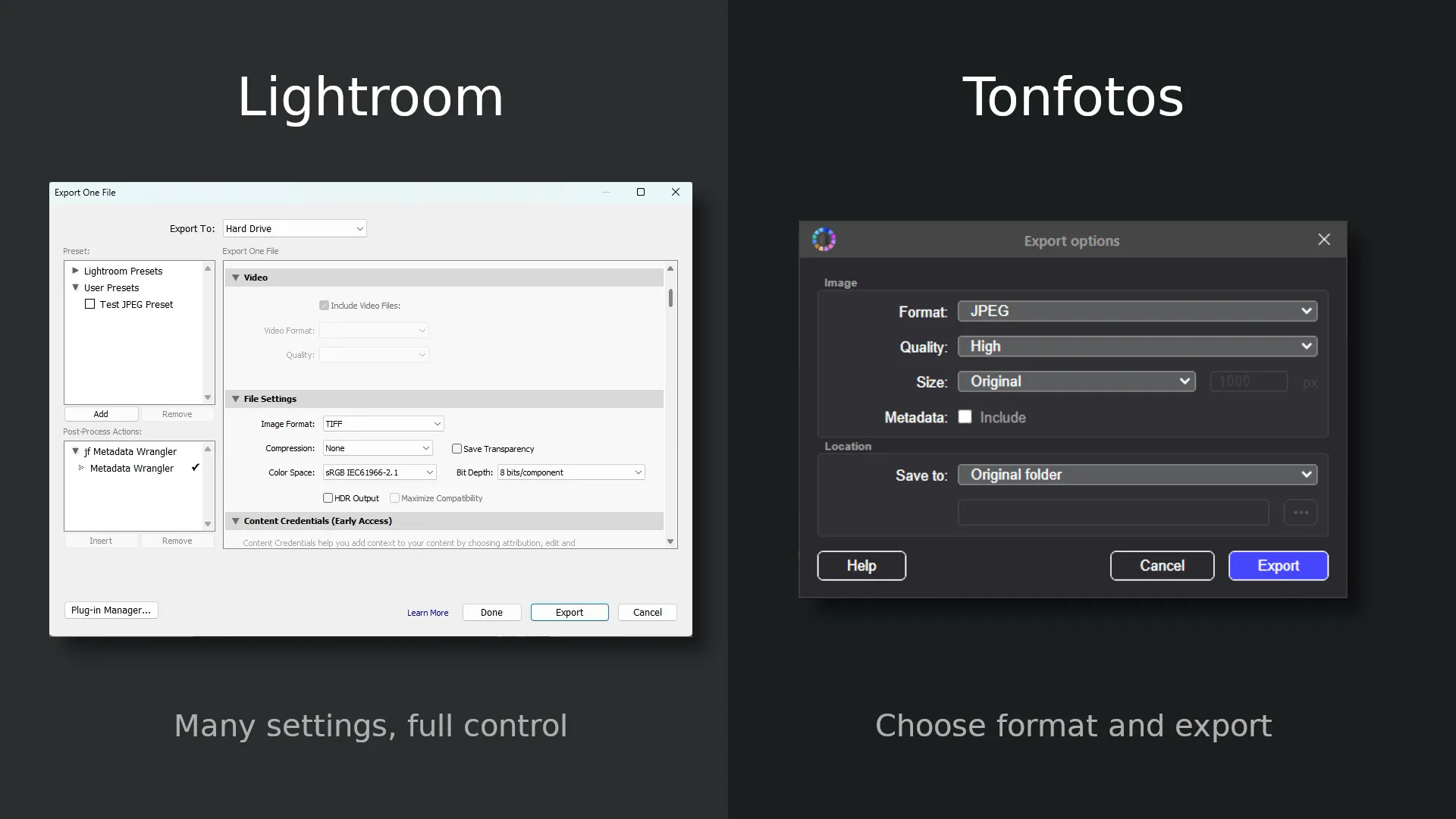

Tonfotos shouldn't be considered "just another image converter." It's a photo collection management tool where format conversion is a logical extension of archive management, not a separate operation.

Unlike Lightroom or Capture One, which are more focused on editing rather than managing digital images, Tonfotos has a simpler and more intuitive interface.

At the same time, the program is really convenient for solving various tasks related to converting and sorting photos or other images.

- Bulk photo conversion without manual processing of each file.

- Preserve all metadata when exporting.

- Selecting images before conversion.

- Preparing "web versions" of photographs.

- Cataloging after conversion. Images remain part of the overall media library, rather than being transformed into a chaotic collection of files.

The program can fully meet the needs of website, blog, and small media project owners, where photographs are not disposable content, but a long-term digital asset.

Conclusion

In 2026, choosing the highest-quality image format is no longer a matter of habit or compatibility with everything. It directly impacts the visual perception of content, the efficiency of data storage, and readiness for future display technologies.

However, the right format alone is only part of the solution. Equally important is how you manage your images after shooting: do you preserve metadata, can you quickly prepare website versions, and is it easy to access the archive months or years later.

This is where tools that treat conversion not as a one-time technical operation, but as part of a unified workflow, come into their own. The approach implemented in Tonfotos allows for more than just re-encoding files; it also preserves the structure, context, and value of images as digital assets. This is especially important for blogs, websites, and media projects where photographs are reused, updated, and scaled along with the content.